When Jan Middendorp’s ‘Dutch Type’ was published in 2004, a veritable wave rushed through the German graphic design scene, which directed our view toward the Netherlands for quite some time. One year later, a similar publication passed by almost unnoticed: « Histoire du graphisme en France », by Michel Wlassikoff (2005). A major reason for this might have been the language barrier; while ‘Dutch Type’ had been written and published in English, the history of French graphic design first appeared in French alone. Since 2006, though, an English version has been available, which could extend our horizon across the Rhine.

Over 320 large format pages, Michel Wlassikoff introduces us to the major lines of development in the graphic arts in France, and acquaints us with the fields’ prominent and less prominent protagonists. The title of this anthology is chosen consciously and has a programmatic intent: not the history of French graphic design is told, but the history of graphic design in France, to which many a designers with roots in other countries also contributed.

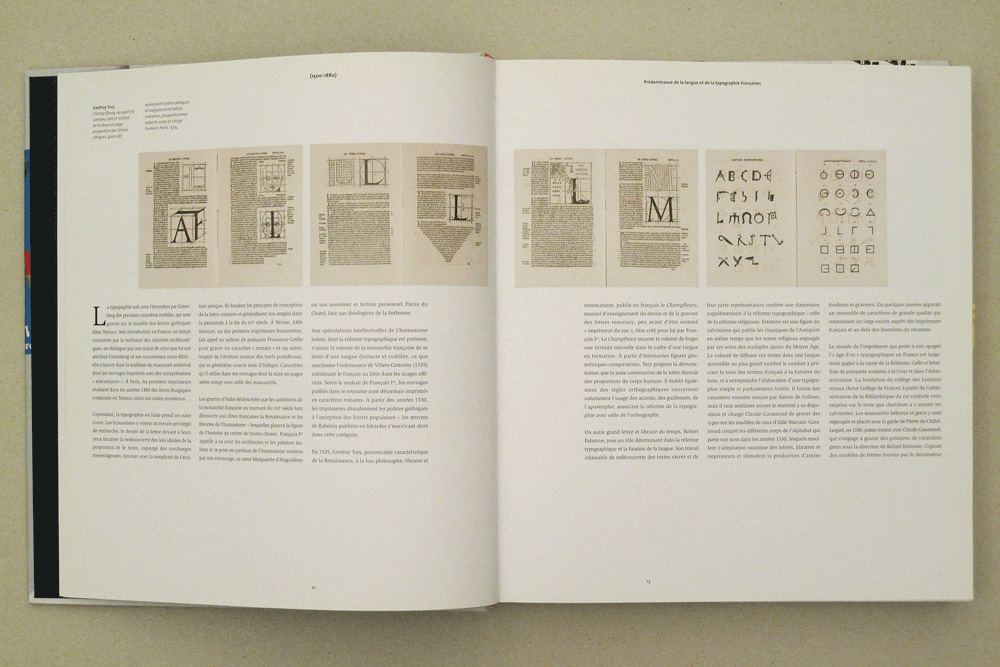

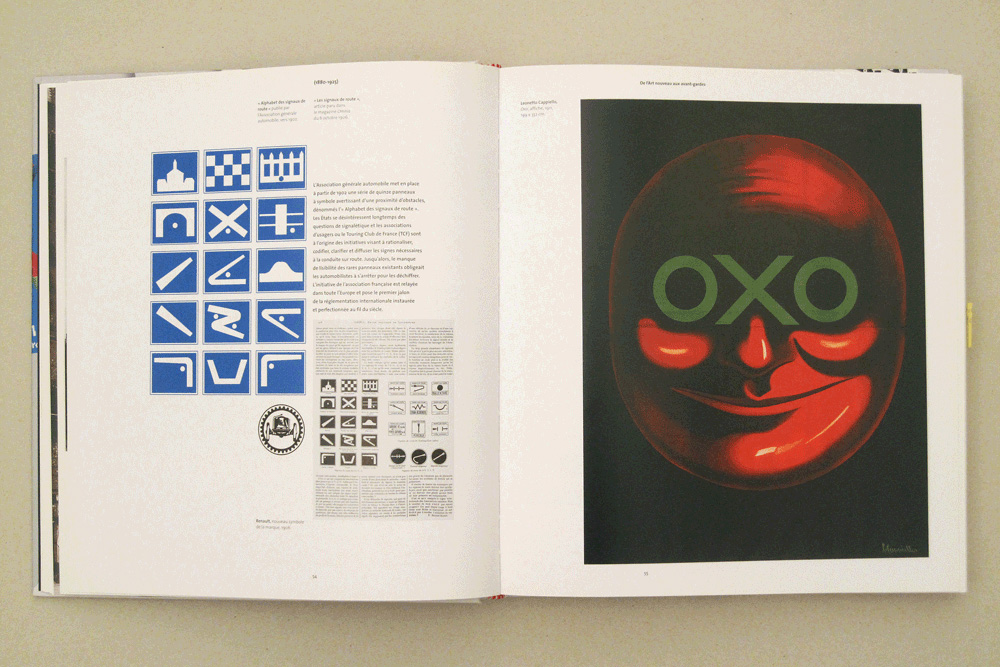

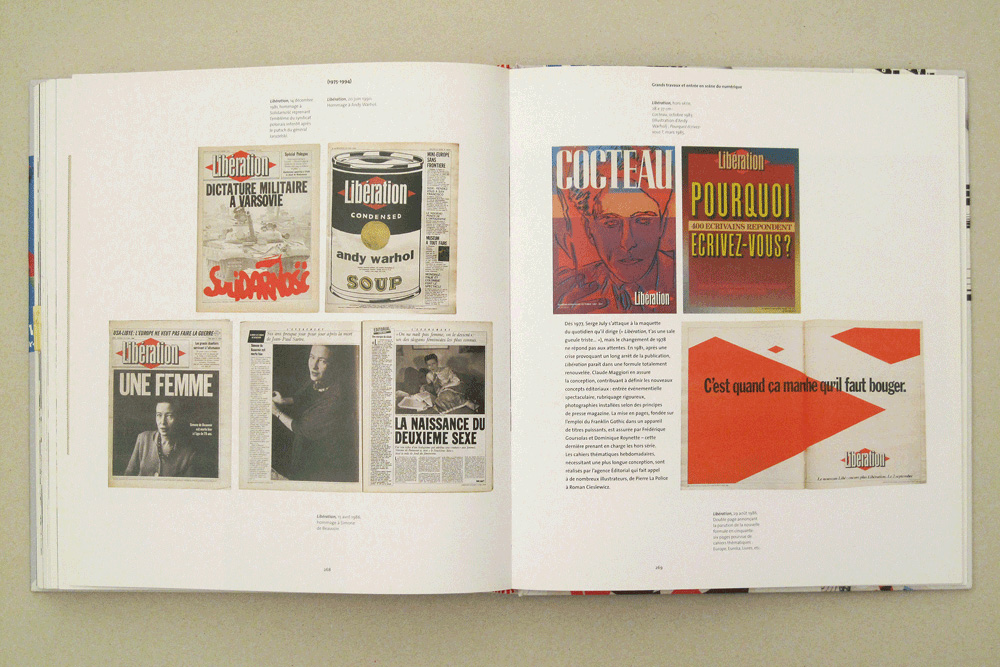

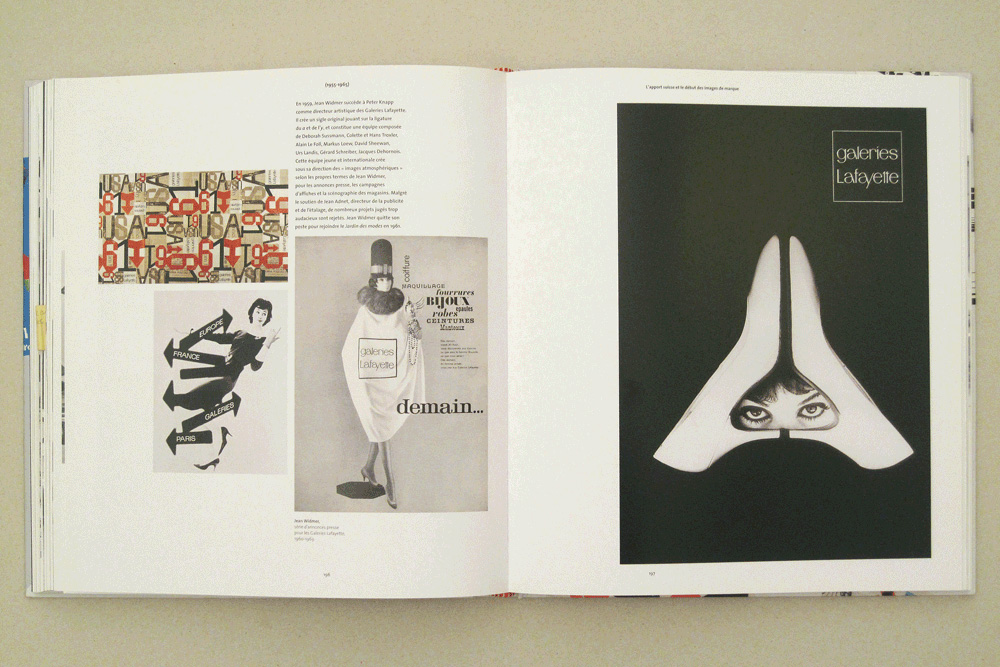

The—in my humble opinion—fairly infelicitous design of the hardcover by EricandMarie should not keep anybody from opening this book. Inside, Sophie Costamagna (conception, art direction) and Marie-Christine Gaffory (execution) deliver an appealing piece of work. In each case, the nine chapters start with an extensive article that—illustrated by pictures of smaller scale—explains the developments in a given period. It is followed by picture-oriented spreads with reproductions of excellent quality and silent legends meeting the standards of art history. Every now and then the coffee table section is enhanced with short explanations or references by the author. This way Wlassikoffs’ book perfectly manages the balancing act between imparting knowledge and offering visual delight.

Histoire du graphisme en France is divised in the following sections:

— The predominance of French language and typography (1500 to 1880)

— From Art-nouveau to Avant-garde (1880 to 1925)

— From Arts-décoratifs to the Union des artistes modernes (1925 to 1930)

— From occupation to Alliance graphique internationale (1940 to 1955)

— The Suisse contribution and the emergence of brand images (1955 to 1965)

— From dissent to the conception of new surroundings (1965 to 1975)

— Grands Travaux and the entrance of the digital medium (1975 to 1994)

— Extension of the Graphic Zone (1995 to 2005)

The ‘Story of graphic design in France’ is less specifically focused on typography than ‘Dutch Type’ was. Nevertheless, type design and lettering plays the leading part in this book. It is fabulous to see how media-unspecific the development of letterforms and their usage is showcased: specimens of typefaces for book printing and jobbing, hand-drawn letterings on posters, inscriptions on buildings and messages expressing opposition, written by individuals in public spaces, equally entered the selection.

The chapters on pre-war Modernism in France and on the developments following 1968 should be the ones of most interest to the German reader, as these differ considerably from the German-speaking sphere. It is a well-known fact that there was no Bauhaus in France. Less known in Germany is that France had a modernist movement of its own. The way in which these differed in both countries emerges when observing two exhibitions that paralleled each other in Paris in 1930:

‘The French presentation, carefully directed by René Herbst and Mallet-Stevens, arranged the works according to their authors. […] Aside from posters and prints only a few works had been realized on order of third parties from the economic and industrial world, in general terms the moveables shown were prototypes. In contrast the Bauhaus showed a collective presentation under the title An apartment block of ten stories which designated a workers’ cooperative. The moveables came from industrial production. […] The comparison of the two exhibitions document on the differing nature of the Modernist movement in France that is characterized by confluent individual approaches, busy with constituting an oeuvre, emphasizing “individualism”. In contrast, the collective prevailed on the German side, social commitment and synthesis, with its totalitarian tendencies.’ [Histore du Graphisme en France, page 75]*

The second time period where one can easily track the considerable divergence between France and Germany is the span between 1965 and 1975, when the Swiss School and American strategy started to set the tone in France as well, regarding corporate design and visual communication, whereas illustration and bande dessinée (comic strips) witnessed a significant upswing and established themselves securely in the graphical culture of France. Especially surprising and momentous for the French state is how bad things looked in this period for innovative design projects for governmental institutions. Various tentatives to improve on forms or to design new stamps and bills were rejected or fouled up beyond all recognition by the administration. This way a key commissioner for landmark projects—as is so typical in the Netherlands, for instance—was absent. In the middle of the seventies, to put it flatly, French graphic design split into a commercial half—that meanwhile in parts hit rock bottom—and an anti-commercial half, which wanted to work exclusively with cultural and political content.

These are just two examples of discoveries from this book that I picked as representatives for many instructive paragraphs in Michel Wlassikoff’s text. In closing, I would like to point out to the extensive bibliography at the end of Histoire du graphisme en France, which offers far more than one hundred thematically sorted entries and makes the book a solid foundation for any research within the field.

— — — — —

* This review was based on the French edition and the passage cited is translated from the original. // ♥ I want to thank Dan Reynolds for his revision of the English text. // This article first appeared on “Republic of Letters” in February 2011. Find its German version here (with different pictures!).

Michel Wlassikoff: Histoire du graphisme en France, Paris: Les Arts décoratifs, Dominique Carré Éditeur, Adagp, 2005. Éditions Carré. English edition: Michel Wlassikoff: The Story of Graphic Design in France, Corte Madera: Ginko Press, 2006.